How I Decide What’s Worth Testing in UX Design

During my career as a product designer, I struggled with a recurring question:

What parts of a design truly need testing — and what can safely rely on design patterns and best practices?

Sometimes I’d lean heavily on conventions and proven patterns. Other times, I’d feel unsure and test everything “just to be safe.” And then came the sign-off meetings.

A stakeholder would ask:

“Did we test this flow?”

or

“Are we confident users understand this interaction?”

And honestly — I didn’t always know how to answer.

That uncertainty pushed me to rethink how I approach testing.

The Real Problem: Testing Everything Isn’t Practical

In theory, everything should be tested.

In reality, time, budget, and access to users are limited.

Over-testing slows teams down.

Under-testing creates risk.

What I needed wasn’t more testing — but a clear way to decide what deserves it.

A Simple Framework That Changed My Approach

Over time, I developed a simple but effective framework to decide what to test and how much confidence I can have without testing.

I call it the:

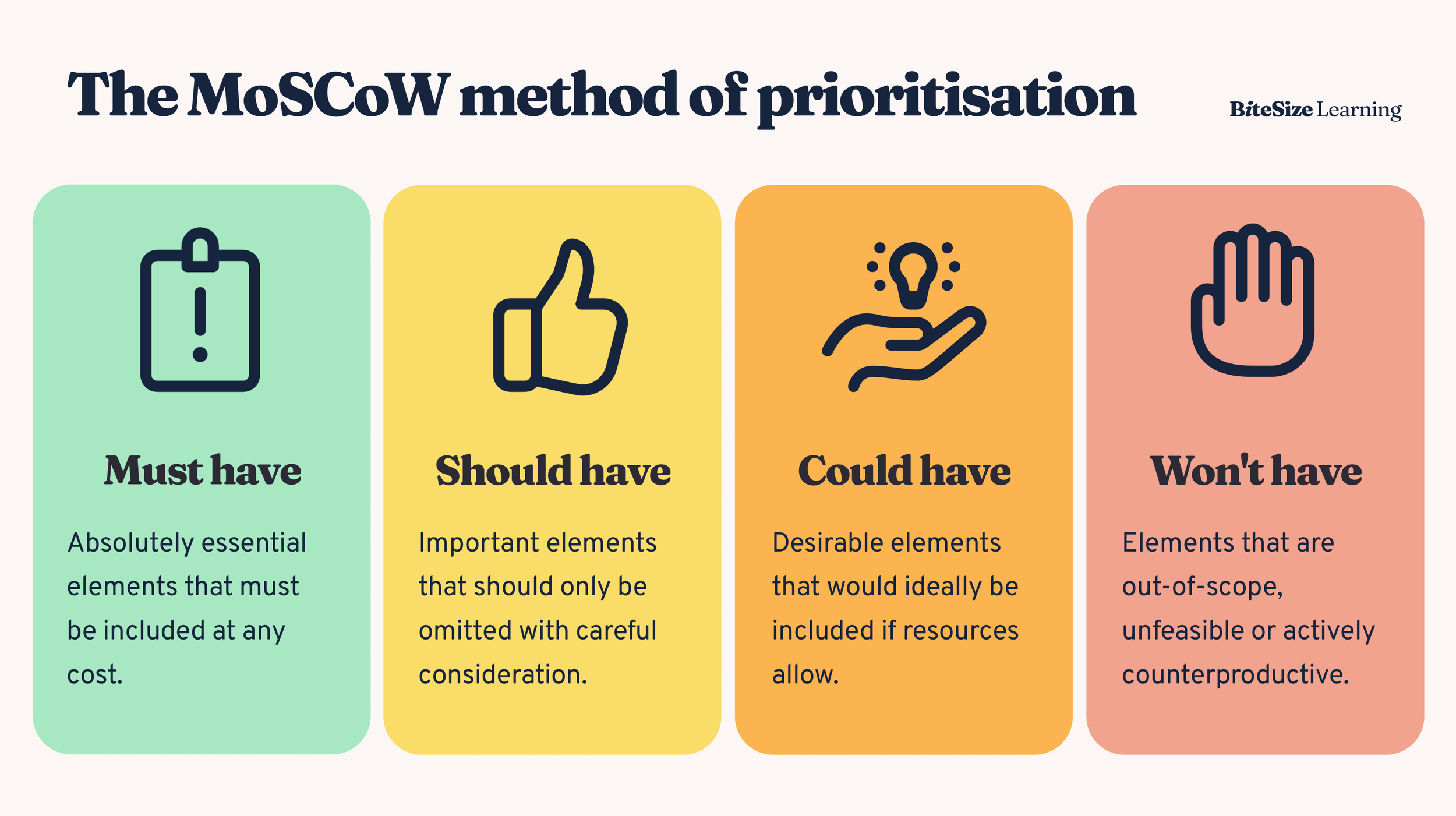

Must / Should / Maybe Test Framework

This framework helps me:

Prioritize testing effort

Explain decisions clearly to stakeholders

Defend design choices with confidence

1. Must Test: High Risk, High Impact

These are the areas I always push to test.

Must test if the design:

Introduces a new or unfamiliar interaction

Is critical to conversion, revenue, or retention

Has serious consequences if misunderstood

Examples:

Checkout or payment flows

Onboarding that blocks user access

Destructive actions (delete, cancel, unsubscribe)

Here, best practices are not enough. Real user feedback is non-negotiable.

2. Should Test: Medium Risk, Some Uncertainty

These are areas where patterns exist — but context matters.

Should test if the design:

Combines multiple known patterns in a new way

Targets a new user segment

Has multiple possible interpretations

Examples:

Filtering and sorting logic

Empty states with strong calls-to-action

Complex forms

If time allows, I test.

If not, I validate through reviews, heuristics, or quick internal checks — and I’m transparent about it.

3. Maybe Test: Low Risk, High Confidence

These are areas where testing adds little value.

Maybe test if the design:

Uses well-established design patterns

Has low impact if misunderstood

Is purely cosmetic

Examples:

Button placement following conventions

Standard input fields

Minor visual adjustments

Icon choices with labels

Here, best practices + design systems + experience are usually enough.

How This Helped in Stakeholder Conversations

Now, when someone asks:

“Did we test this?”

I don’t panic.

I can say:

“This fell into our ‘Should test’ category. We didn’t run user testing due to time constraints, but we validated it using proven patterns and cross-functional reviews.”

Or:

“This is a ‘Must test’ flow, and here’s what we learned from users.”

The conversation shifts from defensiveness to decision-making.

Why This Framework Works

This approach:

Creates shared expectations

Builds stakeholder trust

Reduces over-testing

Makes design decisions more intentional

It turns testing from a checkbox into a strategic tool.

Final Thought

Good design isn’t about testing everything.

It’s about knowing what needs evidence, what needs judgment, and what needs speed.

Having a clear testing criteria helped me move from uncertainty to confidence — and made sign-off meetings a lot less stressful.